Climate change impacts are visibly worsening around the globe and implementing mitigation and adaptation strategies requires unprecedented international cooperation. Historically, decision-makers have worked together to address climate change through multilateral and international treaties that have domestic policy implications for the signatories. In the past, the United States played a leading role in climate negotiations through diplomatic engagement and adoption of domestic policies to address climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), passed August 2022, presents an opportunity for the United States to renew its status as a global climate leader. In preparation for the 27th Conference of Parties taking place this November, this GCSE essay offers a retrospective to provide historical context for multilateral decision-making on climate change and examines the role of US leadership in the upcoming negotiations.

Historical Context of Multilateral Climate Treaties

In 1990, the United Nations initiated formal negotiations surrounding climate change and greenhouse gas emissions in response to growing international concern by the scientific community and the public. These discussions culminated in the establishment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit. Enacted in 1994, the governing body of the UNFCCC is the Conference of the Parties (COP), which meets annually and serves as a platform for evolving climate negotiations. At this time, the UNFCCC has almost universal membership with 198 countries having ratified the treaty and are Parties to the Convention (What is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change?, n.d.).

The primary goal of the UNFCCC treaty is to set long-term objectives to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations "at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system" (What is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change?, n.d.). While the United States played an important role in the primary negotiations surrounding the treaty, it did not support binding greenhouse gas reduction commitments and ultimately, the treaty did not include legally binding emissions targets.

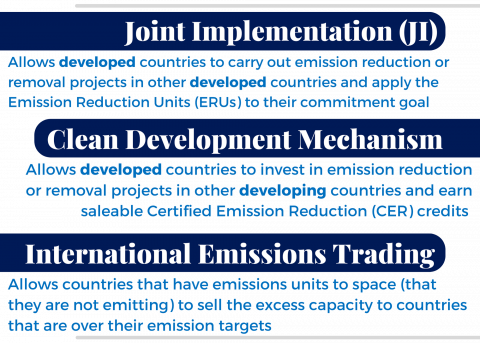

At the first COP 1 in 1995, the UNFCCC parties established binding greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets for developed countries, which included the United States. The resulting treaty is known as the Kyoto Protocol and was formally adopted in 1997 at COP 3. In addition to sustainable development, energy efficiency, renewable energy, and other focus areas, the Kyoto Protocol included flexibility measures, such as joint implementation, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and international emissions trading, which were focused on reducing net emissions by 5.2% by 2012 (What is the Kyoto Protocol?, n.d.). In the end, the Kyoto Protocol contained emission reduction targets for developed countries, but no new commitments for developing countries. Eventually, the United States signed but did not ratify this treaty.

At the first COP 1 in 1995, the UNFCCC parties established binding greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets for developed countries, which included the United States. The resulting treaty is known as the Kyoto Protocol and was formally adopted in 1997 at COP 3. In addition to sustainable development, energy efficiency, renewable energy, and other focus areas, the Kyoto Protocol included flexibility measures, such as joint implementation, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and international emissions trading, which were focused on reducing net emissions by 5.2% by 2012 (What is the Kyoto Protocol?, n.d.). In the end, the Kyoto Protocol contained emission reduction targets for developed countries, but no new commitments for developing countries. Eventually, the United States signed but did not ratify this treaty.

In 2015, the UNFCCC parties convened at COP 21 and developed what became known as the Paris Agreement, which included a legally binding framework. The Paris Agreement recognizes the shared global responsibility for combating climate change and has the objective of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. Furthermore, the framework of the Paris Agreement provides global support with financial assistance, technology development and deployment, and increased capacity building for developing countries. In recognition of the diversity of emissions contributions as well as resources available in each country, the Paris Agreement does not establish universal emissions reductions for the parties. Instead implementation is based on nationally determined contributions (NDC) that are submitted on five year cycles. NDCs are based on the best available science and are a collection of emissions reduction targets, measures, and policies that outline how the country will reach their emissions reductions to achieve the goals of the treaty (The Paris Agreement, n.d.).

At the onset of the Paris Agreement, President Obama signed the treaty without Senate advice and consent, thus the United States became a party to the agreement when it was formally adopted in 2016. In June 2017, President Trump announced the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement which went into effect November 2020. Subsequently, President Biden resigned the Paris Agreement on his first day in office in January 2021 and officially rejoined in February 2021, demonstrating a renewed intention of engaging in international climate commitments (Lattanzio et al., 2021).

Contemporary U.S. Climate Policy and its Global Influence

Although the United States has been deeply involved in previous international climate treaties, it still accounts for more than 22% of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions, making it the single largest contributor to climate change historically (Climate watch (CAIT): Country Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data, 2014). In this context, it is pivotal that the United States actively re-engages in climate diplomacy to accelerate domestic, as well as international, climate commitments.

The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) marks the most significant legislative action that Congress and the administration have taken to address climate change. The IRA includes historic short- and long-term investments into emerging clean energy technologies, emissions reductions, climate adaptation, and market-driven decarbonization. Through these measures, the United States is expected to make substantial progress to deliver the Biden Administration’s 2021 NDC, which established a goal of emissions reduction by 50-52% below the 2005 emissions benchmark by 2030. Furthermore, the goals of the most recent United States’ NDC goals focus on funding towards $1 billion of international climate financing along with emissions reduction targets for transportation, energy, and manufacturing sectors (USA Country Summary, n.d.). Unfortunately, the IRA alone will not allow the United States to meet its 2030 NDC target of cutting emissions in half. In addition to falling approximately 10% short of their goal for emissions reduction, the United States has thus far failed to execute pledged contributions of $11.4 billion annually to international climate financing by 2024. Thus, local, state, and federal leadership will need to take supplemental legislative action to meet emissions targets and avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) marks the most significant legislative action that Congress and the administration have taken to address climate change. The IRA includes historic short- and long-term investments into emerging clean energy technologies, emissions reductions, climate adaptation, and market-driven decarbonization. Through these measures, the United States is expected to make substantial progress to deliver the Biden Administration’s 2021 NDC, which established a goal of emissions reduction by 50-52% below the 2005 emissions benchmark by 2030. Furthermore, the goals of the most recent United States’ NDC goals focus on funding towards $1 billion of international climate financing along with emissions reduction targets for transportation, energy, and manufacturing sectors (USA Country Summary, n.d.). Unfortunately, the IRA alone will not allow the United States to meet its 2030 NDC target of cutting emissions in half. In addition to falling approximately 10% short of their goal for emissions reduction, the United States has thus far failed to execute pledged contributions of $11.4 billion annually to international climate financing by 2024. Thus, local, state, and federal leadership will need to take supplemental legislative action to meet emissions targets and avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Looking internationally, given the United States’ substantial foreign policy influence, strategic engagement of key nations can advance the global climate agenda towards equitable emissions reductions and investment in climate adaptation and resilience. If international decision-makers are able to connect clear and conclusive scientific evidence to climate policy ahead of the COP27 in November, significant advancement on this complex issue can occur to protect communities most at risk.

Sources

- Climate watch (CAIT): Country Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. World Resources Institute. (2014, April 10). Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.wri.org/data/climate-watch-cait-country-greenhouse-gas-emis…

- Lattanzio, R. K., Leggett, J. A., Procita, K., Ramseur, J. L., Clark, C. E., Croft, G. K., & Miller, R. S. (2021, October 28). U.S. Climate Change Policy. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46947

- The Paris Agreement. United Nations Climate Change. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-a…

- USA Country Summary. Climate Action Tracker. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/usa/

- What is the Kyoto Protocol? United Nations Climate Change. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol

- What is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change? United Nations Climate Change. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/what-is-the-united-nations-fram…

Opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the GCSE or its members.