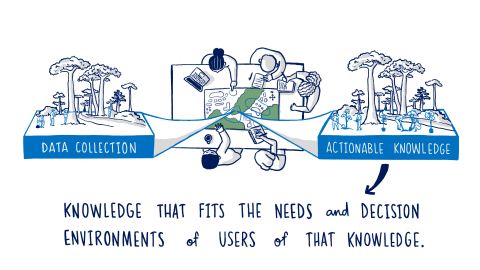

Science should help inform solutions to the many urgent societal challenges we face, from climate change to sustainable development, to combating disease and improving public health, to creating sustainable and secure food, water, and energy systems, to stemming biodiversity loss, and much more. While basic and applied science are important, informing solutions to solve these urgent societal challenges requires actionable knowledge, knowledge that fits the needs and diverse contexts of users of that knowledge.

While all knowledge has value and is potentially useful, science doesn’t generally become actionable if it is produced by scientists or other knowledge producers working by themselves. Rather, science becomes actionable when producers and users of science work together to create actionable knowledge. It is the interaction between knowledge producers and knowledge users that distinguishes the production of actionable knowledge from other ways of doing science, which generally involve much less collaboration outside the academy and are more disciplinary focused.

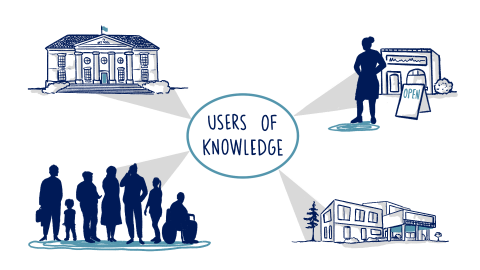

When we talk about engagement, we mean iteratively working with those who use knowledge to make decisions. Users of knowledge can be individuals, groups or communities, public or private organizations, or entities that may need scientific information. It is important for producers of science to understand who the potential users of the science are so those users can be engaged in the scientific process.

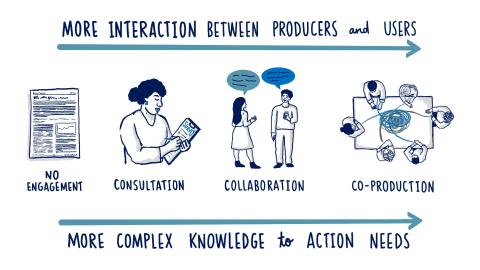

It is also important to match the type(s) of engagement with the needs for actionable knowledge production, as engagement may be more or less time consuming for and empowering of producers and users of knowledge depending on the purpose or goal of the engagement. There are a variety of engagement types available from consultation to coproduction:

- Consultation requires less time from both producers and users because it involves fewer engagements, and the engagements are less intensive. Consultation type engagements help when the needs for moving knowledge from potentially useful to usable require a smaller lift, such as iterating to produce information in a format or form that is actionable. For example, researchers attempting to understand the best ways to communicate methods of disease prevention (e.g., handwashing) might present different versions of informational flyers to community groups to receive feedback on ways to increase the understandability and effectiveness of communication for disease prevention, and then revise or recreate these products based on this feedback.

- On the other end of the spectrum is co-production. Co-production involves a process of deep, iterative engagement between producers and potential users of knowledge from research inception to question generation, refinement of methods, to interpreting and summarizing results. Beyond producing actionable knowledge that meets user needs, this kind of deep engagement creates and sustains spaces for mutual learning and for valuing different types of knowledge and ways of knowing. Continuing with the example of public health, researchers would work together with community members, medical professionals, and public administrators to identify the public health challenges then co-develop research questions attuned to community needs, partner on data collection and analysis, and co-produce and implement holistic solutions.

- Collaboration falls in between consultation and co-production involving ongoing interaction between producers and users, but often with a narrower, well-defined focus determined through a collaborative process. For example, collaboration might encompass a round of moderated workshops with producers and users to collaboratively define a set of plausible scenarios about climate change, community development, behavior and disease characteristics to inform disease transmission models.

While there are a variety of engagement types available from consultation to co-production, the choice in what type of engagement to use ultimately depends on the overall goal or purpose of the engagement relative to the needs for actionable knowledge production and considering the need for more ethical research approaches.

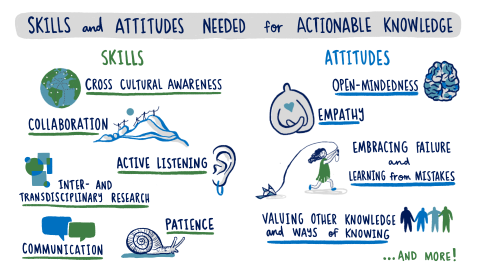

Increasingly, scientists and students seek to engage in more ethical, equitable, inclusive, and culturally-appropriate research practices. Yet the disciplinary knowledge and skills that most students and faculty learn on university and college campuses today are not the same as those needed for successful production of actionable knowledge. Scholars interested in actionable knowledge production often need to be able to work across disciplines and to draw on communication, facilitation, and cross-cultural competencies to be successful in collaborative and transdisciplinary research. Beyond these skills and competencies, actionable knowledge production benefits from researchers having soft skills and intangibles, like the ability to listen well and to empathize with and value the knowledge and experience of others.

Recognizing the need for accessible information, I worked with the GCSE as the Science Advisor for Actionable Knowledge to help craft the upcoming Actionable Knowledge video series. The series of short, digestible videos are meant to be a helpful resource for students and faculty to learn more about what actionable knowledge is and how to produce it. By showcasing the stories of students, faculty, and professionals working on actionable knowledge production, the videos also highlight the skills and attitudes that help facilitate the production of actionable knowledge in ways that are more accessible, inclusive, and culturally appropriate. Finally, the stories illustrate how actionable knowledge production is helping to inform solutions to a myriad of societal challenges from sustainable, resilient buildings to solutions to mitigate urban heat and flooding, and to new scientific advancements and collaborations to ensure sustainable water resources. I hope this introduction to actionable knowledge opens up new pathways for scientific thought and more ethical, actionable research for a more hopeful future.

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the GCSE or its members.

Funding was provided by the NASA Applied Sciences Program, Grant Number: 80NSSC21K1202. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.